Letters

In “Meet the Creatives” [Fall 2009], editor Elizabeth Padjen expressed succinctly the position that the Commonwealth of Massachusetts has embraced with regard to the Creative Economy: “… support of the arts is not indulgence; it is vital to fostering creative thinking and the innovation that fuels our economic system.”

Massachusetts’ revolutionary spirit has led to over 400 years of innovations across all sectors of the economy, and the driving force behind those innovations is creative thinkers. Governor Patrick has emphasized the growth of the creative industries as key to our innovation-economy efforts by appointing the first-ever Creative Economy Industry Director and signing the Creative Economy Council Bill. We have forged key collaborations with creative industries, including the launch of the Design Industry Group of Massachusetts (DIGMA), which connects the design community with policy-makers and leading industries.

Bridging the gap between our creative talent and business people, industrialists, technology experts, entrepreneurs, academicians, and the entire innovation ecosystem will help maintain Massachusetts’ rightful place as one of the leading “ideas” economies of the world. It also helps ensure that the design talent that comes to Massachusetts for a world-class design education stays on to work in the design professions in the Commonwealth. This is why we’re excited about DIGMA’s upcoming “Design and Innovation” events as a way to expose many of our other industries to the innovation that can come from “design thinking.” We hope these sessions will not only be the beginning of a sustained conversation about the importance of design to the growth of businesses across the spectrum, but will also eventually put more of our designers to work by growing jobs both within and outside the design industries.

Gregory Bialecki, Secretary of Housing and Economic Development, Commonwealth of Massachusetts

The Creative Economy [Fall 2009] is a powerful catalyst for innovation in our science- and technology-based industries. This belief has guided our work at the Massachusetts Technology Collaborative’s John Adams Innovation Institute in the context of seminal projects that have nurtured and strengthened our Creative Economy. These efforts have included a key conference organized by The Salem Partnership; assistance to the Berkshire Economic Development Corporation, leading to the establishment of Berkshire Creative; and involvement in an initiative by Massachusetts College of Art and Design that led to the founding of the Design Industry Group of Massachusetts (DIGMA).

In addition to appreciating their intrinsic value for the human condition, the expression of the spirit, and the building of the symbolic and material worlds around us, the Creative Economy industries and professions are fundamental to the vitality of the Massachusetts innovation economy. As Beate Becker comments [in “Industrial Strength”], David Edwards convincingly argues [in “Catalytic Converter”], and Peter MacDonald illustrates [in “Arts & Minds”], we know that when artistic creativity, design thinking, and science and engineering expertise come together, visions emerge of novel products with exceptional form and function. This is why opportunities and spaces for interaction among artists, designers, scientists, and engineers are so important. And this is why education in the arts, design, and the humanities starting in K-12 is as important as science, technology, engineering, and math.

Congratulations to ArchitectureBoston and to the individuals and organizations featured in the Creative Economy issue who work hard every day to transform the Creative Economy industries and professions from our best-kept secret into one of Massachusetts’ most important assets in the global economy.

Carlos Martínez-Vela PhD, John Adams Innovation Institute, Massachusetts Technology Collaborative

Thank you for the article “The Creative Entrepreneur” [Fall 2009]. I appreciate your recognition of the often-overlooked importance of creative businesses. As a consultant to creative companies in the Boston area, I relish the validation that your article provides.

As creative professionals, we often work more nimbly, networking with other creatives to form business task teams, and then dismantling them when they are no longer needed. Our efficiency, innovativeness, and aesthetic impact are exceptionally valuable to communities. However, despite this, we still work primarily in silos and, as such, lack the social and political power that brings recognition and benefits.

I hope that this article will inspire others as it has inspired me to make a commitment to working more collectively with other creative entrepreneurs to assure that our voices are heard in unison.

Inge E. Milde, Inge Milde & Associates; Entrepreneurship faculty, Tufts University

“The Creative Entrepreneur” by Christine Sullivan and Shelby Hypes [Fall 2009] provoked many thoughts as I reflected on my own journey as a sole proprietor.

Those who enter the Creative Economy do so for reasons beyond financial prosperity. Most have very little business knowledge or experience; with eyes firmly set on creative goals, they rarely understand the true risks involved. They have heard about “cash flow” but did not realize that it may mean long periods of time between earning and receiving their income. When new opportunities disappear with a downturn in the economy, they wonder what will happen next. In the present economic situation, many are experiencing the downside of the high risk = high reward equation.

The article illuminated common misconceptions, including the fact that sole proprietors are not counted in the state economic reports (perhaps 20 percent of the workforce). Without this data, how can we understand the true state of the economy? How can we gauge the economic recovery without this knowledge?

What should the government do? Personally, I do not want to be “bailed out.” I would prefer more creative solutions to keep struggling sole proprietors solvent, such as restructuring tax laws to use current revenues to estimate taxes, rather than past years’ (higher) figures; simplifying the process of hiring employees for small businesses; and carefully studying the impact proposed mandates would have on small business (and job) growth.

Most importantly, as creative entrepreneurs, we need to collaborate to help each other thrive as business owners. In bad economies, new businesses often flourish: the newly unemployed often find the smallest opportunity may be enough to begin a new firm, like a forest regrowing after a wildfire. We need to be there to help them grow, through mentoring and knowledge-sharing.

Bill Whitlock AIA, Waltham, Massachusetts; Chair, BSA Small Practices Network

I was delighted to see your broad coverage of the Creative Economy in the Fall 2009 issue. As the president of Midcoast Magnet, a Creative Economy networking organization based in Camden, Maine, I am very tuned in to the relationship of people and places. Camden is a short sail down the coast from Northport, home of Swans Island Blankets featured in Deborah Weisgall’s “Arts & Minds” article.

With companies like Swans Island Blankets as an example, Maine is becoming a great place to do business. We have hardworking, creative people who can now compete on a global basis while choosing to live in one of the most picturesque environments on the planet. One of the challenges we have is in re-purposing the existing buildings that give Maine some of its character to meet the needs of a 21stcentury place of business. At the same time, architects and builders in Maine are challenged with renovating our aging housing stock to meet the demands of environmentally-conscious consumers while protecting the historical architectural palette that helps to define the Maine brand.

In November, Camden will host the Juice 2.0 Creative Economy conference [“Building Maine’s Innovation Networks”], which will weave together the arts and culture, along with technology and entrepreneurship. With over 40 breakout sessions featuring the best of Maine businesses, we’ll be developing creative networks and discussing issues related to quality of place and entrepreneurship. I invite your readers to join us!

Skip Bates, Midcoast Magnet, Camden, Maine

I just received the Fall 2009 issue of ArchitectureBoston. By what stroke of good luck someone put me on your mailing list, I will never know. But your publication is always an eye-opener. As an architect in both New York and Hartford, the view you present of Boston and Boston-area design is significant. In short: the quality of the design work is generally higher by a long shot than the design work in New York, and certainly in the Hartford-New Haven area. That says something good about Harvard, MIT, and the other Boston-based design schools.

Sidney Vaneyck Sisk, Hotel Design and Development, New York City and West Hartford, Connecticut

Catalytic Converter

With feet planted in the worlds of art and science, Harvard professor David Edwards is promoting new ways of catalyzing creativity and innovation.

Cloud Place (The Cloud Foundation); Boston. Photo by Joel Veak.

Jeff Stein: In his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas Kuhn notes that great scientific advances are intuitive. It’s only after the initial stroke of intuition — that “Aha!” moment in which scientists are really only guessing at something — that the left hemisphere of the brain kicks in and the experimentation, which is what most people think of as science, takes over. You’ve invented the term “artscience” to describe a kind of creative thinking. Are these concepts related?

David Edwards: Yes, absolutely, although Kuhn’s work focuses on very recognizable “Eureka!” moments in the history of science. Artscience suggests that the process is less linear. Great innovations often come from two kinds of responses to a problem. One is the process of intuition and induction, which requires comfort with uncertainty and is often image-driven. The other frames the problem by simplifying it to a set of conditions that are identifiable and solvable — the scientific process of making a hypothesis, looking at the data, and drawing conclusions, which are often not what we expected and so require a new hypothesis. The artistic method and the scientific method fuse in key moments of innovation. The moments that are most memorable are the ones when we’re standing in front of a blank page saying, “I don’t really know what to do.”

Jeff Stein: Your interests now seem to focus on the problem of that blank page and the idea that it often makes sense to cross the cultural divide between art and science and begin to fill in the blanks from the other perspective.

David Edwards: I increasingly look back at my childhood as a fount of information about everything I’m doing right now. If you look at how we learned as children, you realize that we were constantly moving from one environment, which we would get to know, to another, in which we had no clue. We went from crib to living room to school, constantly entering new environments and needing to throw away a lot of what was familiar in order to discover something new.

The hallmark of creative people is that they try to shock themselves. They try to go back to that state where they’re throwing themselves into an unknown environment. I may be very familiar with the scientific environment, yet I find it very catalytic to my creativity to immerse myself in the artistic environment. Then, once I get adapted, I run back to the scientific environment and shock myself, like jumping into cold water, and suddenly I’m much more sensitive to what it is to be a scientist, to what that lab means, to all these things that I just grow numb to after a while. So I run back and forth. I think creative people often tend to run across this conventional art/science divide.

Jeff Stein: You’ve even placed yourself in that kind of situation in your personal life, dividing your time between Paris and Boston.

David Edwards: That’s absolutely true. It’s easy to point to all of the challenges of our age, but one of the benefits of the world today is the ability to live simultaneously in two very different cultures; that is a kind of art/science divide for me.

Jeff Stein: You’re also crossing divides in your professional life. You were trained as a chemical engineer and have taught at MIT and Penn State as well as Harvard. And now you are also jumping back and forth into the worlds of commerce and nonprofits.

David Edwards: The reality is that, from an early age, I was really never comfortable in an educational environment, even though I ended up being very educated. I was often very frustrated with school. That probably started at age eight when I wrote my first novel. My teacher took it home, and her son dropped an ice-cream cone on it. I constantly had the feeling that what mattered to me didn’t really matter in my school. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, I moved to Israel for four years. I had this idea that I could just live another life, and ended up becoming a very theoretical scientist, really loving my work. And I wrote. I’ve always been interested in writing, but it was a very private kind of passion.

Jeff Stein: You kept a pretty low-profile until the late ’90s when it seems that you had your own “Aha!” moment. What happened at that point?

Manga art by Junko Murata; excerpted from Whiff © 2008 by David Edwards; published by Éditions Le Laboratoire (distributed in the US by Harvard University Press).

David Edwards: Something very surprising happened to me: I published an article in the Journal of Science about delivering drugs, such as insulin, to the lungs in special kinds of aerosols, after which a venture capitalist approached me. He wanted to bet on my idea. I was at Penn State at the moment; I had left MIT a couple of years before that. I had no experience in industry and was both flattered and then frightened by the prospect that if I wanted to follow that opportunity, I would have to leave the scientific research environment that I had grown accustomed to, my comfort zone. We founded a company, Advanced Inhalation Research, which was sold within a year; the condition of sale was that I had to stay on for two years.

After that three-year period, I came back to Harvard to teach. I had left the university thinking I knew everything that I needed to know, and was coming back feeling as if I’d discovered everything that really mattered while I was away. I thought hard about how I could bring that experience to my students, this different way of learning.

One important element was that somebody had made a bet on an idea that I had, that someone believed in it enough to do that. And it pushed me, really pushed me to an edge, to take risks I never would have taken, just to prove my idea. So I started to teach a course where I encouraged kids to dream — I kind of bet on them.

This was during the Larry Summers years at Harvard — he was encouraging a lot of interdisciplinary dialogue on campus. I had started to write a novel more seriously, and my wife and I had started the Cloud Foundation to bring arts programs to urban kids. As I became more and more involved in the arts, I noticed that most of the university interdisciplinary dialogues were among the scientific disciplines; the humanities in general were not included. So I started a dialogue with a group of people, about 11 of us, from a music theorist to a composer to an architect to a medical doctor; people who, like me, rather than being driven away from this art/science divide at Harvard, were attracted to it for different reasons. All of us were very different, but we had similar experiences in that we were all celebrated by our institutions, but none of us had really been nourished by them. And we had all fled our institutions at key moments in our creative process. I suddenly understood why I had been doing so many different, weird things in my life, and what the writing had actually represented for me. The outcome of this reflection was a book, Artscience, and the idea of Le Laboratoire, an experimental center promoting artscience collaborations.

Jeff Stein: So you became homo faber, he who makes, not just he who thinks. And as a result, your title is not professor of biomedical engineering, but rather professor of the practice of biomedical engineering.

David Edwards: It’s ironic, because, 15 years ago, I was a very theoretical scientist. I have since learned that discovery is an active process. It’s an active confrontation with a mysterious, evolving, unimaginable world.

Jeff Stein: There has been a lot of talk lately about the sorts of people and the kinds of activities that make up the Creative Economy — which at some basic level is about this process of discovery and the translation of ideas to some useful purpose: products, jobs, positive change.

David Edwards: We’re seeing an incredible rediscovery of the power of human creativity, and the possibility to transform our world in potentially beneficial ways. The challenge is how to integrate that into institutions, particularly into educational institutions. How do we teach that? The Creative Economy is a huge reality here in Boston, one that doesn’t exist in such a dynamic way in many other places in the world. Our challenge, right now, is how to grow that.

Jeff Stein: As you’ve thought about the creative process, have you found any commonalities that suggest that there is a teachable formula? Is there, for example, an identifiable moment when you switch brain hemispheres or when the artistic trumps the scientific?

David Edwards: I’m really skeptical of the “how to” approach to being creative; all the really creative people I know have never followed that sort of path and probably would not even want to analyze their creativity. But here’s one observation: I think that creative people are very sensitive to their dependence on environment, both the human, or architectural, environment and the intellectual, or creative, environment. So they tend to put themselves in stimulating environments. Creativity seems to fall into phases: a starter or conception mode, a translation mode, where we’re developing an idea, and a realization mode. We gravitate toward the environments that support those phases.

Jeff Stein: In other words, we are possessed of brain, voice, and hands, and we’re working with one of them at a time, but all three of them together get us where we want to be.

David Edwards: Yes — that’s an interesting way to put it. One problem in our understanding of creativity is that our social and cultural institutions are mostly designed to measure and encourage manifestations of ideas, which often substitute for creativity itself. When a book is published, or a product is manufactured, or a symphony is performed, the key moments of the creative process are invisible. In the course of a creative endeavor, you’re going to make lots of mistakes. But creators don’t see them as such — they’re producing prototypes, so of course there are mistakes; you learn through multiple iterations. That may go on for days, weeks, months, even longer. But that’s when everything’s happening; those are the key moments. So I think for the creative process to be really alive and active, as it is in a healthy childhood, we need to be frequently thrown into that mode where everything is evolving, where we don’t know where to go next.

Jeff Stein: And that mode is often found in an artistic environment. So, the creative mind can be developed through exposure to the arts, and yet the arts aren’t as valued politically here as in France, where you spend the other half of your life. Can we change that?

David Edwards: There is a need today to demonstrate the value of the arts in America, beyond the ability to sell a work of art to a major museum. The arts are hugely relevant to culture, to humanitarian engagement, and to industry, and there’s a need to integrate the arts into all that we do. The Cloud Foundation is an effort to advance that idea by working with the Boston public schools. My wife and I did not grow up with money. Selling the company was very exciting, of course, but it was also disorienting — not in a negative way, but just in trying to understand it. We made a decision right away that we wanted to give away at least half of what we made, and we wanted not to just write checks but to be actively challenged by the process. So we created the Cloud Foundation, which has since worked with thousands of kids through its headquarters at Cloud Place on Boylston Street in Boston.

The Foundation has recently entered into an exciting new phase with the recent launch of our first ArtScience Innovation Prize competition for Boston public high school students. Its purpose is to help them develop the tools for cross-disciplinary learning and creative thinking. We provide them with up to 100 breakthrough ideas, very “blue sky” art and design ideas at the cutting edge of science. They then work with mentors — scientists, artists, and entrepreneurs — and participate in workshops at Cloud Place and the Idea Translation Lab at Harvard to help them think about how to translate these ideas into project concepts, which could be new products, for-profit companies, museum exhibitions, nonprofit organizations, anything. Teams will present their ideas to a panel of judges this fall, and the winning team will receive $100,000 and a trip to Paris to continue its work at Le Laboratoire. The goal here is to bet on kids, to get them to learn early on that their passionate commitment to ideas that cross boundaries can be transformative.

Jeff Stein: Besides the Innovation Prize, what goes on at the Cloud Foundation on a daily basis?

David Edwards: We talk to 10,000 kids a year but work principally with the hundreds of kids who come in for after-school art workshops and programs. We sponsor exhibitions and events and work in partnerships with other organizations in the city. In general, Cloud Place is a kid place where kids are the curators. Working with kids means dealing with problems of kids, so there are lots of sit-down conversations and moments with kids from struggling neighborhoods in Mattapan and Lynn in which you sometimes hear things that are very powerful and sometimes difficult or hurtful. The Cloud is a window into the life of our young generation.

Jeff Stein: You have a sister organization, Le Laboratoire, in Paris, which is more for adults and sponsors projects between artists and scientists.

Le Laboratoire; Paris. Photo by Bruno Cogez.

David Edwards: The Lab, as I call it, is a cultural institution in the center of Paris that is closely partnered with Cloud, Harvard University and, increasingly, Trinity College in Dublin. It includes exhibition space and a design prototype store, where you can buy things that you can’t buy elsewhere. As prototypes, they may not work perfectly. There’s also a food lab, a wild place where we’re producing food innovations with the renowned chef Thierry Marx, who we think of as a kind of culinary artist. Our challenge is to invite the public into art as process, as opposed to art as outcome, which is the fundamental distinction of a cultural lab versus a cultural museum. We do a few experiments each year with major artists and scientists. The idea is to create a new kind of translational lab, in this case a cultural lab, which is creating value that we can measure. We’re doing an experiment at the Louvre right now. I’m hopeful that the Lab will invite major investment from both government and venture capitalists.

Jeff Stein: Your new novel Whiff is a fictional account of an actual process that led to a new product from the Lab just last spring.

David Edwards: Yes. The product is Le Whif, an aerosol inhaler that delivers the taste of chocolate, without actually eating the chocolate. Zero calories. The novel was written with the idea of engaging the public in the drama of the creative process, which is hard to convey in an exhibition space. The food lab led to thinking about art and food and science, which led to the idea that maybe you could inhale food — I do know a lot about aerosols. I gave the idea to some students and they inhaled substances like mint and pepper — although the pepper was a disaster. At the end of the semester they said, “This is really cool, but we can’t stop coughing.” So we figured out how to get around that, and then included a Nespresso Whiff Bar in a culinary art exhibition at the Lab. It made a lot of news — people were enchanted by the idea even though many coughed. So we improved the design and now finally have a commercial product. We planned to sell it in our LaboShop and at Colette, a high-end store in Paris, and on the Internet. But then a young, former student, who is a brilliant entrepreneur, decided to start a viral campaign. That was a Friday in early April. By Saturday, our Internet traffic had doubled. Two weeks later, we were being asked for interviews on Oprah and Good Morning America and weeks later we’d received inquiries from distributors in 40 countries around the world.

Jeff Stein: You’re describing creativity as a constant state of metamorphosis.

David Edwards: Or to turn that thought around, it is at the frontier of knowledge where we all become artists. Metamorphosis is confusing, chaotic; a scientist at a frontier of knowledge is not sure of anything. Take Judah Folkman, a man I really admired, a pioneer in the field of angiogenesis in cancer research, which focuses on blood supply to tumors. For years and years, he stood at a frontier with no proof that this frontier was really what he thought it was.

Jeff Stein: With your novels and products and teaching and the Cloud Foundation and the Lab in Paris, you’re really kind of a bridge builder. The Japanese have a term for this: hashi. It means the end of one thing and the beginning of another. And that can be a bridge. It could be chopsticks, which is the end of food on the plate and the beginning of food in your mouth.

David Edwards: I love that concept; it’s another way of thinking about metamorphosis. Our civilization is undergoing a metamorphosis right now, and at the same time I think that we all feel pulled toward this frontier of knowledge. It’s a very chaotic, confusing era. But this is precisely the time in which the arts have a major role to play in every sector of society. The arts can teach us how to embrace the chaos and turn it into a moment of enormous creativity.

Arts & Minds (Part 4 of 4)

Profiles in the Creative Economy: An economy isn’t about policy; it’s about people.

I spoke to four people who solve old problems with new methods, who discover old solutions to new problems. They are combining interests and information in innovative ways. In doing so, they are building new communities. None of this work happens in solitude. It all requires a critical mass of resources: intellectual, technical, economic, and artistic. While the reach of these enterprises is international, they are rooted in local communities that encourage cross-fertilization between different kinds of expertise, that find new paths for knowledge and intuition. Art and commerce are once again becoming more comfortable with each other. In this new atmosphere we are seeing the results of a convergence of these two basic human impulses. It is a whole new world.

Peter MacDonald: lead artist for Rock Band, Harmonix Music Systems

Photo by Elliot Clapp.

Rock Band is one of the incredibly popular videogames developed by Harmonix Music Systems, Inc. in Cambridge, Massachusetts (others include Guitar Hero and Amplitude). In Rock Band, you and your band play gigs in clubs across the country and around the world, move up from van to tour bus, from simple chords to whole songs, from Seattle to Shanghai, doing everything (musically, at least) that real rock bands do, including hitting the camera. Playing these games, you navigate intense, intricately detailed visual and acoustical worlds. Peter MacDonald’s first job after college was as an architectural draftsman; after a year, he left that field to develop games.

Deborah Weisgall: Your industry has gone from cutting edge to mainstream in about 15 years. What was it like to invent games when you started out; how does it compare to what it’s like now?

Peter MacDonald: A small cadre of game developers has been plugging away since the late ’80s; I joined the industry in 1995, working for a startup. It took five or six years to publish our first game, and our team was a pretty scrappy, disorganized bunch. Everyone had a wide swath of responsibility and a lot of room for creativity because we were making up our own intellectual property as we went along. I was an environmental artist, applying some of what I’d picked up from architecture and a lot of what I’d picked up from fantasy novels to create a virtual 3D world. It was pretty fun, but in retrospect, we wasted a lot of time and didn’t really know what we were doing. Most of us were right out of college. In 1995, you couldn’t find experienced developers in Boston; there was a lot of talent coming out of the schools here, but not a lot of leadership. The whole company might be 20 or 30 people, mostly young, white, nerdy males.

Now the games I work on have budgets that are 10 times larger, and the teams and the company I work for are all 10 times larger. When I joined Harmonix four years ago, we had roughly 30 employees; now we have roughly 300. The game industry has matured; we have adopted standards and practices from other creative industries, and we strike a healthier work/ life balance. We’re making better games in a shorter amount of time and without as much stress. One downside, depending on how you look at it, is that an individual’s creative bubble of ownership has gotten smaller. On my first game, as an inexperienced artist, I created a whole world, almost entirely at my own whim. A junior environment artist on my team now will be able to build a handful of interior spaces under very close supervision.

Deborah Weisgall: How important is the location of Harmonix? Do you benefit from the critical mass of musicians and artists and high-tech people here?

Peter MacDonald: Absolutely. Harmonix was founded by two MIT graduates. Our art director went to the Rhode Island School of Design. I went to UMass Amherst. Many of our artists went to MassArt or RISD. However, most of the game industry is on the West Coast. In Seattle, if you were to go into a Starbucks and announce that you were starting a game company, you could be handed the résumés of several experienced developers before you finished your latte. Here in Boston, you need to attract a mix of raw talent out of all the universities, plus experienced developers who are willing to move back here. It’s kind of tough to find the people you need, but this is starting to change because companies like Harmonix are meeting with success and growing. I hope that young people in school in Boston will start looking locally before jumping on a plane to Seattle right away.

Deborah Weisgall: How do environments and characters grow?

Peter MacDonald: Harmonix’s games are unique in that the character and environment design are not closely integrated with the core gameplay. They have a supporting role. As a result, the artists have pretty free rein. We collaborate in small groups: five or six character artists on a game, with one leader and somebody like me overseeing all art. In terms of process, it’s pretty straightforward. We determine our needs, start drawing concepts, do group critiques, then more formal orthographic drawings to guide the 3D production. We hook up all the technology that will control the art assets, then it’s tested and fixed. By the time the consumer sees the game, dozens of people have “touched” it.

The technology is our medium, but technology does not dictate our aesthetic goals.

Deborah Weisgall: Perhaps you can talk about the scale of your audience, their attention span, turn rate: the kinds of things you think about when you make games.

Peter MacDonald: The biggest games sell millions of copies every year; when you think about architecture on that scale, you’re talking bridges, airports, and stadiums. Big stuff. I had a very small role on the design team for FedEx Field in Maryland. The stadium took perhaps 10 years from conception to opening day; Rock Band took one year. Then there’s the lifespan; we hope that the Rock Band franchise will last for decades, but that’s not typical in the games industry.

When we develop games, we spend a lot of time discussing the player experience. We use terms like “difficulty ramp,” “play cycles,” “hardcore,” “casual,” “stickiness,” “story-driven,” “achievement-driven,” and whether something is “family-friendly” — or not. We try to identify a target audience, though if you are working in an established genre, the audience has already shown itself. We spend a great deal of time on the core musical interface and experience. Every little detail is debated. How fast do screen elements move? How saturated are the colors? How much information is too much? We basically operate on the knife-edge of human sensory cognition. That’s how the game becomes challenging. If it moved any faster, or required the player to parse one more piece of information at the hardest levels, then it would become impossible and cross over from fun to frustrating.

Deborah Weisgall: How do you combine art and technology?

Peter MacDonald: The technology is our medium. Our products are experienced via a television screen and audio system, and interfaced by an instrument-shaped controller. That structure and the available technology define our limits. Technology is constantly changing, so we have to be adaptable; we are constantly learning. We try to exploit any new technology that might improve our game, but technology does not dictate our aesthetic goals. We might paint or draw characters that appear more detailed than we could achieve in the game for real, but it gives us a direction to aim for. The artists collaborate closely with the engineers who write our graphics software. We ask for the moon, and they work to give us the closest thing to the moon that the hardware can manage.

Rock Band 2 screenshot courtesy Harmonix Music Systems, Inc.

Books

Imagine a Metropolis: Rotterdam’s Creative Class 1970–2000 by Patricia Van Ulzen (010 Publishers, 2007)

Imagine a Metropolis is a gossipy book about the role of Rotterdam’s artists, planners, and impresarios in the economic and physical development of the city since 1970. Although the book delves too deeply into insider stories to appeal to most readers, this detailed account of the cultural history of Rotterdam has important lessons for capitalizing on our own post-industrial past.

Since the 1920s, artists, architects, and cultural commentators have created a robust representation of Rotterdam as the modern doppelganger to the historical capital city of Amsterdam. In the 19th century, Rotterdam’s port eclipsed Amsterdam in size and importance and, in the 20th century, it emerged as the largest in Europe. Port functions and associated industries that sprang up along the River Maas injected the city and environs with a character that was mythologized by 20th-century photographers and writers. In addition, the Rotterdam school of architecture, as exemplified by the Van Nell factory and architects like Mart Stam and J.J.P. Oud, was contrasted with the contextual brick architecture of the contemporary Amsterdam School. The bombing of Rotterdam in World War II by both the Allies and Germans (reflecting the strategic importance of the port) meant that most of the city was rebuilt in a postwar Modernist style, thus fulfilling prewar Rotterdam’s image of itself as a modern metropolis. In the early 1960s, the auto-dominant planning that characterized postwar Rotterdam was criticized by an emerging cultural elite that initiated several projects to reintroduce a pedestrian scale and natural landscape elements to the central city. But by the late 1970s, the edginess of Modernist Rotterdam was re-embraced by independent filmmakers and proponents of New Wave music who found the gritty industrial landscape the perfect backdrop to their aesthetic.

Ironically, the port authority became the biggest champion of the underground creative class by giving a group of architects and artists a former waterworks facility for use as studio and performance spaces in the late 1970s. Called Utopia, this same group implemented Ponton 010, a floating theater and bar that seated 1,100 people. Ships and cranes served as the moving backdrop for concerts and other kinds of performances. As a result, the port landscape became the galvanizing spectacle of modern Rotterdam.

While Boston is more similar to Amsterdam, there are useful comparisons between Boston and Rotterdam including the role of the underground music and arts scene in the 1970s. Like Rotterdam, Boston is also exploring strategies that reconcile the working waterfront with a revitalized urban culture and needs to consider initiatives that better coordinate official cultural policy with a vital and entrepreneurial underground culture. Van Ulzen makes a convincing case that representations of a city, even if they are amped up to the level of a stereotype, can become self-fulfilling.

Creative Economies, Creative Cities: Asian-European Perspectives by Lily Kong, Justin O’Connor, eds. (Springer, 2009)

Why are signs of urban regeneration so unevenly distributed? Some cities — Boston, for example — have reinvented themselves, while others — such as Detroit — have not. Readers of Jane Jacobs may have suspected the cause, but we needed economist Richard Florida’s seminal 2002 work The Rise of the Creative Class to validate it. Florida’s research shows that cities that host creative individuals and enterprises do better than those that don’t. It’s only a short beat from there to the thesis that cities can improve their economies by making themselves hospitable to creative industries. Seven years later, Florida has become the rock star of urban resurgence, and there is nary a beleaguered city in America that does not aspire to a creative economy.

Creative Economies, Creative Cities, an edited collection of articles by academics from Europe, the Far East and Australia, puts Florida’s thesis in global and historical context. The book mines a rich vein of debate that began long before 2002 about the effectiveness of the Creative Economy idea. It seems that Florida is less an innovator than a synthesizer and popularizer whose genius, like Henry Ford’s, is to integrate advances by others and put them into production.

The book is a kind of echo chamber for academics and policy-makers, with authors citing each other’s works and taking positions on sometimes narrow questions of economic and cultural policy. The authors worry about how to define creativity, whether it resides in the individual or in the collective enterprise, how to measure its economic impact, the effectiveness of creative clusters, how exportable creative policy is, and how to avoid homogenization and gentrification. Defining creativity broadly to encompass technological innovation encompasses videogame developers, the focus of an article that addresses why all Asian cultures except Japan are imitators rather than innovators.

Most of these pieces originate in social democracies in northern Europe or the more authoritarian national cultures of China and Singapore, where government has a big footprint and there is less debate about whose culture is being promoted. So why has the Creative Economy thesis become so popular here in the US, where we tend to rely on private philanthropy rather than government to enrich domestic life? Perhaps because it provides a pragmatic rationale for public support for cities and for the arts which overcomes the culture wars about elitism.

But the book’s many competing voices suggest that these policies may prove trickier to implement than they appear. Once you frame the goal as economic development, cultural excellence becomes secondary. And it’s hard to engineer serendipity anyway, so maybe all you can do is to create the circumstances that allow it to arise and hope for the best.

The American College Town by Blake Gumprecht (University of Massachusetts Press, 2008)

Blake Gumprecht is passionate about college towns. He has spent most of his adult life in them and has written a lively and engaging book that should be required reading for the many architects and planners in Greater Boston charged with mediating the divide between town and gown, from Berkeley to Bangor and hundreds of places in between.

A professor of geography at the University of New Hampshire, Gumprecht begins with an excellent history of the college town and why it is a uniquely American phenomenon. He focuses a keen geographer’s eye on the subject and has definitely done his legwork, traveling to dozens of places and interviewing a full range of students, faculty, administrators, politicians, and townies. He provides exhaustive — sometimes too exhaustive — details about the demographics and makeup of college towns, and how to distinguish one from a place that merely has higher education in its midst. But it’s sometimes difficult to understand why he lavishes attention on certain places at the expense of others — we hear far too much about Ithaca, New York and the Kansas towns of Lawrence and Manhattan, for example. Oddly, for a man who teaches in New England, our region is strangely underrepresented in the book, as is the South. Geographic diversity, anyone?

Gumprecht and his fellow collegetown habitués seem at times a little too satisfied with themselves: “Youthful and eclectic, unusually cosmopolitan for towns of their size, with more bookstores and bars per capita than other cities, the business districts of college towns display a free-spirited distinctiveness…”

But having provided this overly gushing description early on, he redeems himself later by pointing out how college-town residents seem to personify our national culture of contradiction. They see themselves as bastions of tolerance, eccentricity, and freedom, but don’t want rowdy student neighbors; they claim to be for the underdog, but don’t want any housing development that might attract new residents or erode their own property values. He takes to task the left-leaning residents of a major California college town as follows: “There is ample evidence to suggest that support for liberal causes in Davis has been unreliable, selective and motivated more by selfishness than concern for the greater public good.” Go Gumprecht!

The author ends on a positive note — not only are college towns not going anywhere, but they also stand to be the winners in the ongoing national competition for the “knowledge economy.” But college towns are like “artsy” neighborhoods — once they become a bit too smug and affluent, they lose the funky authenticity that made them special to begin with. It is this funkiness that Gumprecht celebrates, and he’s not afraid to point out that, sometimes, the enemies of local collegetown character are the very ones who claim to be its champions.

Channel Center, Fort Point

Other Voices

My six-year old neighbor most accurately describes what’s different about living in an artists building. He says, “All the grownups will play with you.”

Our particular building, Midway Studios, is discipline-diverse. The live/work lofts house artists of all kinds: painters, sculptors, writers, photographers, poets, filmmakers, actors, dancers, and musicians; several collaborations (and my current employment) have started with conversations in the elevator. To rent here, you must be certified as a Boston artist through an anonymous review process administered by the Boston Redevelopment Authority. This helps ensure the caliber of work produced — we are home to two Guggenheim award-winners and several published authors. Apart from peer pressure, this is an incentive to make serious work, since certifications are periodically renewed and required for housing. Cease to meet the standards and you must move out.

Loft living is not ideal for all artists. It is expensive, and the changing development landscape makes our future uncertain. Some people leave because they can’t get their kids into local schools; some simply yearn for green space. We have few conventional features here and have forged a kind of artificial environment to create a more balanced reality.

When there is a snowstorm, Fort Point is quiet and unplowed — perfect conditions for cross-country skiing. Phones ring and text messages go out with invitations to venture outside. Making our way across parking lots and along the Harbor, we discuss city politics, our families, national news. We talk about the changing neighborhood, bet on which developments will actually get finished, reminisce about the old days over hot chocolate.

Mostly we extend invitations for shorter trips — to the hardware store, to do laundry, to have a glass of wine. Summer brings other invitations, for activities that might seem more at home in a traditional New England town. We have a neighborhood softball league and hold potluck barbecues on rooftops. We sometimes paddle through the locks and up the Charles River in kayaks kept in parking garages. A movie series is screened outdoors onto sheets in our tiny park; the previews are often our own short films, and some of the most popular features are Hollywood films we have written or acted in or movies that have been shot in Fort Point (Adaptation, Gone Baby Gone, The Departed).

We compensate for living and working in one room by treating the neighborhood geography like a large house. Landmarks are referred to as if they were rooms. A group of us meet for coffee most mornings in “the kitchen,” a spot on the banks of the Channel. We talk about recent openings, share recipes and advice. We play nicely, although envy or long-standing grudges about being passed over for a show are occasionally revealed over scones. Our “great room” is a local bar with ’70s paneling, a piano and TV, and — always — familiar faces. We sometimes buy milk there, or even the occasional tomato or piece of fruit, from sympathetic staff who understand the cold cruelty of a long late-night walk to the 7-Eleven on the Harbor. Barter is official currency in Fort Point, and we extensively trade services and artwork in exchange for food or equipment.

Some of us are here because we don’t fit anywhere else. The eccentricities of our work life — “days” that begin at 7 pm, the tendency to go out in public in torn, paint-stained clothes — aren’t well tolerated by most people. Some of us are here because we’ve been kicked out of studio space, marriages, or countries. If you are broken, Fort Point is a good place to get put back together.

It’s like living in a village full of extended family. We’re related by art. Generations are marked by the date you settle here, lineage determined by your standing in the art world. Like most families, our clan is strange (but reliable), and occasionally susceptible to squabbles and cliques. But you always have a place at the table if you want to come down for dinner.

Photo by Eric Levin; concept by Rob Smith.

Ephemera

Reviews of lectures, exhibitions, and events of note

Guggenheim Museum; New York, New York; May 15–August 23, 2009

In celebration of the 50th anniversary of Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic building, the Guggenheim is hosting its first exhibition of his work. Featuring 64 projects — both built and unrealized — this exhibition offers an intimate view into his design process through 200-plus original drawings as well as newly commissioned models and digital animations.

According to Phil Allsopp, president/CEO of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Wright completed over 1,100 designs; the archive is vast enough to supply an exhibition of this size annually for 110 years. The curators chose what they believe are Wright’s best drawings, and the usual suspects are in attendance (Unity Temple, the Taliesens, and of course the Guggenheim itself), but his unbuilt projects, many on display for the first time, are perhaps some of the most fascinating.

Of his design for the San Marcos-in-the- Desert Resort, a victim of the 1929 crash, Wright said, “I have found that when a scheme develops beyond a normal pitch of excellence, the hand of fate strikes it down.” This held true for the captivating Gordon Strong Automobile Objective and Planetarium, the hand of fate being an unhappy client who declined to build it. Its form was an upside-down predecessor to the Guggenheim — modeled in section for the exhibition, complete with twinkling stars. Also stunning are Wright’s drawings and a new topographic model of the Huntington Hartford Sports Club/Play Resort that daringly cantilevers from the museum’s wall.

While visitors of the Guggenheim often take the elevator and then meander down its spiraling ramp, this exhibition is arranged in a loosely chronological order from the rotunda floor upward. It is only fitting to culminate at the top, mirroring the path of Wright’s career and legacy.

Image caption: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; 1943–59. Ink and pencil on tracing paper. © 2009 The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona.

Directed by David M. Edwards; Produced by EMotion Pictures, 2008; DVD, 82 minutes

A somber mood prevails throughout Sprawling from Grace, Driven to Madness, a primer on the urgent need to reform our culture’s automobile-dependent ways. A who’s who of national visionaries in energy, transit, and sustainable development tell the story, with appearances by some familiar Bostonians (David Dixon, Michael Dukakis, Tad Read).

Attempts to lighten the mood with nostalgic, black-and-white clips of the American love affair with the automobile and suburban life instead leave one wistful for simpler times. Though it tries, the film fails to deliver the emotional weight of a call to action.

More unfortunately, it neglects the ready availability of solutions. Bad news is emphasized over the good despite the positive data now emerging from cities (such as Portland, Oregon) in the forefront of the sprawl battle; images of today’s success stories — walkable shopping streets, mid-rise districts with transit stops — are fewer and less compelling than they could be. The Scared Straight model is indeed scary, but fear is not a reliable motivator.

Harvard Graduate School of Design; April 3–5, 2009

One subtext of this conference became clear almost immediately when keynote speaker Rem Koolhaas cursed architects for having no answers. The message was repeated over three days: Attempts to solve design problems by focusing only on architecture are inadequate and ineffective responses to real urban problems in this urban century. Design practice as it has been is over. Design practice must change in order to address pressing issues of climate change, social and economic equity, and health. The way forward was not at all clear, although the range of presenters — architects, historians, humanists, theologians, bureaucrats, academics, agronomists, artists, scientists, inventors, landscape architects, planners, politicians, a university president, a dean, and a mayor — symbolized the core idea that multiple disciplines working together are essential.

Its meaning elusive, the term “ecological urbanism” held an umbrella over everything “sustainable” while emphasizing the urban. The varieties of urbanism referenced over three days ranged from “ethical” and “landscape” to “reconsidered,” “dynamic,” and “user-generated.” The conference was extremely well planned — including an exhibition, forthcoming book, and website with podcasts — yet it conveyed a messy sense of confusion and incoherence, very much a work in progress. The need to craft a new language seemed to be another subtext. Perhaps the unadorned term “urbanism” is an adequate place to start and a useful focus as thinkers come to understand the complexity of the city’s dynamics while being constrained by realizations about natural-resource limits and damage to the environment.

It is good news that the powers that be, including now Harvard as well as the City of Boston, recognize both the need and the opportunity to make important changes to the status quo and to embrace new knowledge, with the understanding that cities and regions must be part of the solution. Alex Felson of Yale University asked the best question: “Is there a way architects can and will take in data and processes of ecology and make a difference?” As the conference made clear, the answer will require architects to adopt a broader stance as engaged creative thinkers and activists finding new ways to bring the knowledge to bear across disciplines, collaborating with peers in every field. It won’t be easy, as Andrea Branzi cautioned: “Interdisciplinarity is not a comfortable affair.”

Arts & Minds (Part 3 of 4)

Profiles in the Creative Economy: An economy isn’t about policy; it’s about people.

I spoke to four people who solve old problems with new methods, who discover old solutions to new problems. They are combining interests and information in innovative ways. In doing so, they are building new communities. None of this work happens in solitude. It all requires a critical mass of resources: intellectual, technical, economic, and artistic. While the reach of these enterprises is international, they are rooted in local communities that encourage cross-fertilization between different kinds of expertise, that find new paths for knowledge and intuition. Art and commerce are once again becoming more comfortable with each other. In this new atmosphere we are seeing the results of a convergence of these two basic human impulses. It is a whole new world.

Susan Williams: creative director of Swans Island Blankets

Photo by Sarah Szwajkos.

Swans Island Blankets is a company based in Northport, Maine that produces handwoven blankets from flocks of local sheep. All the dyeing and weaving is done in an old house, and sheep pastured on a small island off the coast supply thick wool for winter blankets. The designs — single colors, subtle color blocks, and stripes — rely for their effectiveness on the natural shades of the wool and on vegetable dyes. Susan Williams, one of the owners and the creative director, has built an international clientele for their products.

Deborah Weisgall: How have you combined old-fashioned technology with modern marketing?

Susan Williams: I wanted to apply the aesthetic of the product to the company as a whole. There is a great story behind the company — John and Carolyn Grace left law careers in Cambridge to pursue a more satisfying life weaving classic blankets on Swans Island. We’ve moved the operation to the mainland, closer to where we live. The core issue is to introduce the blankets to a broader market without wrecking their integrity. I’ve captured the story on our website and in our printed materials; it’s no baloney when someone understands what “timeless beauty” means. Our aesthetic has substantially helped the company’s growth, which is part of the reason why we receive so much media coverage — we operate on a minuscule marketing budget.

Deborah Weisgall: How do you set goals for growth?

Susan Williams: Our goals for growth are more or less driven by our financial and human resources. There’s been some trial and error and postponing of great products — we produced some coats a couple of years ago that proved too labor-intensive and expensive. We quickly learned what we could accomplish while maintaining the highest standards, given the current scale of our business. We have four looms. Last March, when Michelle Obama wanted to give one of our throws to the prime minister of Ireland, we were lucky that we had a green one already on the loom.

We like to think of ourselves as the Slow Food of manufacturing, which probably sets us apart from other business models. We also offer a blanket hospital for cleaning and repairs. And this summer we introduced a line of yarns for hand-knitting, in colors that are consistent with our aesthetic.

Our aesthetic has substantially helped the company’s growth, which is part of the reason why we receive so much media coverage — we operate on a minuscule marketing budget.

Deborah Weisgall: How would you describe the satisfactions of the business?

Susan Williams: They come from knowing that I am contributing to making products that are genuinely exquisite, practical, and simple. Our customers come from all over the world; they are unimaginably varied.

Deborah Weisgall: What is Swans Island’s impact on the community?

Susan Williams: Obviously, we employ people — and it fits into this place because there are a lot of interesting and talented people running small businesses here. There seems to be a deep understanding and desire for our standard of quality — not only locally, but globally.

Photo courtesy Swan Islands Blankets.

The Creative Entrepreneur

Seven misconceptions about the way we work

What do a self-employed architect, a game designer, and a new-media consultant have in common? They’re all part of the Creative Economy, they’re likely to be proprietors, and they don’t get the recognition they deserve. They’re under-counted, underestimated and under-served — because they are the victims of serious misconceptions.

Promoting the Creative Economy requires a new understanding of creative businesses.

Misconception #1: The Creative Economy is about the arts. Yes, actors, musicians, and visual artists are included, but it doesn’t stop there. The Creative Economy consists of those industries that have their origin in individual creativity, skill, and talent, and that have a potential for wealth and job creation through the generation of ideas, products, or services. How this gets interpreted at a local level varies. In the Berkshires, for instance, tourism and the arts are indeed the backbone of the economy. But in another tourist destination, Essex County, the top Creative Economy clusters include design, research and development, and advertising. The key is in the name: creative. Jobs whose stocks in trade are creativity and innovation are likely to be part of the Creative Economy.

Misconception #2: The Creative Economy centers on nonprofit organizations. In fact, according to a 2008 study of Boston’s North Shore, the Creative Economy represents 10 to 12 percent of that region’s private sector (non-government) employment, providing jobs for nearly 20,000 people through more than 2,000 enterprises. That’s larger than the share of biotech (2 percent) and manufacturing (7 percent) industries within the metropolitan Boston economy.

It is when one combines the impact of the Creative Economy with that of self-employed proprietors and entrepreneurs that this overlooked yet powerful economic engine really picks up steam. In 2006 (the most recent year for which data are available), proprietors represented one out of five jobs in Massachusetts. These are the sole practitioners, husband-and-wife teams, and micro-businesses that are part of our daily business lives. While exact numbers of proprietors among design professionals are not available, one statistic suggests that proprietors are a significant presence in the practice of architecture: among the members of the Boston Society of Architects, there are 475 sole practitioners and 200 firms of two or more employees. Proprietors are flying below the radar for a number of reasons. They may have an Internet business or a home-based enterprise with no physical visibility, especially in towns where the prohibition on home-based businesses has never been changed. They may not have filed a DBA, so that their town or city does not know they exist. Their customer base may not be local, so they have little incentive to join a chamber of commerce or other community business group. And they have few advocates to speak for them.

Misconception #3: If proprietors were important, they’d get more attention in state economic reports. The truth is that, astonishingly, we’re not counting proprietors (who account for one in every five jobs in Massachusetts, remember) at all in state economic reports. That’s because proprietor data are filed only with the individual’s federal tax return each year. When proprietors are considered, the doom-and-gloom story of statewide job losses becomes one that actually offers hope in grim economic times. The number of proprietors in Massachusetts grew 33 percent between 2001 and 2006, an average of more than 35,000 a year. That number was large enough to counter the loss of wage-and-salary jobs and result not in the 2.6 percent decrease in the number of jobs reported in the media for that period, but a 2.3 percent increase!

Although data beyond 2006 are not yet available, it is more than likely that both the number of proprietors and the growth rate of proprietors in many industry sectors are increasing during the current recession. It is during recessions that many laid-off wage-and-salary employees test the waters of entrepreneurship, some out of necessity, some taking advantage of their unemployment to realize a long-held dream.

Becoming a proprietor and joining the Creative Economy is not only an increasingly viable employment option for individuals, but also a source of economic growth for Massachusetts.

Misconception #4: Proprietorships, especially those in the Creative Economy, are not “real” businesses. According to the recently released study Proprietor Employment Trends in Massachusetts: 2001 to 2006, which was also the source of the one-in-five statistic above, proprietors who work alone outnumber those with wage-and-salary employees. This is not to dismiss proprietors with employees; they grew by nearly 28 percent between 2001 and 2006. These are not necessarily one-person, kitchen-table hobby operations. They are small companies who choose not to incorporate for a variety of reasons, frequently taxes. Among them may well be the next killer iPhone application, the next Design Within Reach, or the next Sundance award-winner. More important, not to consider creative entrepreneurs as having real businesses is to buy into a misconception with significant consequences for how local, state, and federal governments allocate resources.

Misconception #5: Most proprietors are people temporarily freelancing until they can get a real job. Those who believe this are missing a dramatic and permanent shift in how we work. There are several factors driving this, the most compelling of which is the Internet. With a desk and a laptop, an individual can now run a global business from home. This could never have happened 20 years ago. Computing power and Internet accessibility have created a “portable economy.” When the restrictions of physical locale are removed, entrepreneurs can collaborate with many more people, extend their customer reach, and draw on a far broader base of resources. They can also work in new patterns. Tina Brown, the former editor of Vanity Fair and founder of The Daily Beast website, refers to the “gig economy” as one in which people don’t hold a single job, but take on assignments or gigs, much as a musician does. Somewhat related to this, the self-employed are increasingly adopting the Hollywood model used in filmmaking — people with the specific skills and talents needed for a project come together for that assignment and then disband.

Misconception #6: People in the Creative Economy are, well, “different.” In some ways, they may well be. But even if they don’t want to be grouped with the “suits” of the business world, artists, designers, and advertising copywriters have a lot in common with their peers in traditional corporate environments: they need business skills and they need political support for their business endeavors. Because the Creative Economy and proprietors are underreported and underestimated, it’s not surprising to find that they’re also under-served. Little research has been done to identify the economic impact of these companies, and no research has been conducted to identify their needs. But, as the director of the Enterprise Center at Salem State College, working with entrepreneurs and small businesses, I have a unique vantage point. I see talented people daily who are seeking skills they need to run their business. I hear them talk about the premium they, as individuals, must pay for healthcare, the limited options they have for retirement savings, their need for tax relief and for better access to credit.

Misconception #7: There’s little you can do. There’s a lot you can do, and it may start by recognizing that you yourself, or the businesses you work with, are part of the Creative Economy. Creative entrepreneurs can form coalitions and associations to advance and support legislation and policy changes that will support their endeavors. Through organizations such as the Creative Economy Association of the North Shore, you can individually and collectively raise awareness of the Creative Economy’s contributions as a sector and of the need to nurture the micro-businesses that contribute to the industry’s vitality. These kinds of businesses have historically received little recognition at the government level.

The growth of the Creative Economy and the increase in proprietor employment in Massachusetts are phenomena not to be taken lightly in their own right. In combination, they tell us we’re looking not at a transitory fad, but at a permanent sea change in how we work. Technology has empowered the creative entrepreneur and opened the floodgates to new opportunities for self-employment. Becoming a proprietor and joining the Creative Economy is not only an increasingly viable employment option for individuals, but also a source of economic growth for Massachusetts.

There is a new recognition of this within the Commonwealth. Massachusetts recently established the Creative Economy Council, chaired by the Secretary of Economic Development, and is the first state in the country to have a Creative Economy Director. The Massachusetts Cultural Council has also been very active in the promotion of this business sector. But the ultimate success of the creative industries in this state depends upon the energy of individuals. We need more voices in the choir. Join in, and help get the word out.

Public Displays of Affection

The Lurker

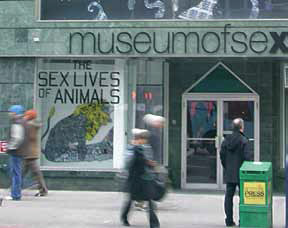

The place: New York City’s Museum of Sex, located in a small nondescript mid-century commercial building in the middle of what used to be called the Tenderloin District.

The shtick: Put it out there. Display it frankly, the way other museums display paintings, or dinosaur bones, or decorative arts objects, or artifacts of war.

1:25 Just inside the front door, a sign says: “LINE FORMS HERE,” but, on a Tuesday afternoon, there is no line. A sign behind the ticket counter: “PLEASE DO NOT TOUCH, LICK, STROKE, OR MOUNT THE EXHIBITS.” People wishing to display this directive in their kitchens are in luck, as the sign has been reproduced on refrigerator magnets for sale in the gift shop.

1:29 The gift shop is cheerfully smutty. Corkscrews shaped like naked women; coasters printed with photos of naked men; an orange juicer resembling a pair of breasts (“Squeeze two halves at the same time”); books about bras and Japanese bondage; The Illustrated Book of Orgies; fur-covered handcuffs; anatomically explicit pasta, origami, balloons, and blown-glass swizzle sticks; and various small vibrating objects including a yellow rubber bathtub duck. A couple is giggling quietly at the back of the shop. “We should get this for Arnie and Sarah,” she says, but his reply is inaudible and they leave without buying anything.

Photo by Joan Wickersham.

1:34 Gallery 1, a bright, open space with windows looking onto Fifth Avenue, is displaying a show called “The Sex Lives of Animals.” Visitors are welcomed by a large white plasticine sculpture of an excited ape. The aesthetics of the show are upbeat and scientific: graph-paperpatterned walls featuring headlines like “Parthenogenesis: Living Without Sex” and “Sexual Cannibalism.” A man and woman in their 60s — tall, both with short silver hair, wearing fanny packs — peer at an exhibit comparing the genitalia of various species. “I’m not certain here which is the male and which the female,” she says, of a large photo showing two barnacles. “Dissection would tell more of the story,” he says.

1:38 Another man — nearby but not too nearby; in this museum, few people gather in groups — whispers to the woman he’s with: “You saw the collection of penis bones?” “Yes, but I didn’t think they had bones.” “Well, I guess maybe in some species they need them,” he answers earnestly.

1:44 Two women in their 20s pause beside a plasticine statue of an orgy involving three white-tailed deer. “Is this for real?” one woman whispers to the other.

1:52 At the back of the gallery, a number of people stand around watching a video about bonobos, Congo apes who, according to the chirpy audio narration, have “a rich and varied sexual repertoire.” The film continues for several minutes — lots of frantic, happy-looking primate action — while the people stand around and watch in solemn silence. The narrator explains that there is often same-sex activity between male bonobos, and even more between females. “The bonobo, our closest relative, lives in a society in which the goals of the human feminist movement have been achieved!”

2:05 Upstairs, Gallery 2 displays an exhibit called “Sex and the Moving Image” — museum-speak for movie sex. In contrast to the white laboratory vernacular of the downstairs gallery, this long narrow room is designed as pure peep show. It’s dark. To the side are a number of little open booths with screens on the walls. The main space is divided into two corridors by a long half-wall suspended from the ceiling and ending several feet above the floor, so that the people standing on either side are hidden from each other except for their feet and a little bit of leg. This suspended partition is studded with screens, each of which runs movie scenes in a constant repeating loop. Loud music pulses through the space, providing an audio cover under which conversation can take place — except that there isn’t a lot of conversation. People stand before the screens, silent, watching the butter scene from Last Tango, the rape scene from Deliverance. Each screen is capped by a blue-lit sign assigning some academic-sounding category: “Mainstream: Same Sex,” “Youth and Virginity,” “Sexploitation,” “Nudist Films.”

2:09 An anguished cry from one of the booths: Greta Garbo as Anna Christie confessing harshly, “Yes, it’s that kind of house. I hate men!”

2:14 Beneath a sign that says “First Experiments,” Hedy Lamarr swims in Ecstasy, Greta Garbo smolders in Mata Hari, Mae West vamps in I’m No Angel.

2:22 “Metaphorical Sex,” says a prissier sign nearby, above a screen running Hollywood clips from the late ’30s through the ’50s, when nothing could be shown but a lot was implied: Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Gone With the Wind, Notorious, A Streetcar Named Desire.

2:31 And just beyond that, from the same era but apparently belonging to a different world, a stag film gallops cheerfully along: woman shows up at man’s door, peels down, does stuff, then prances naked to the phone, dials a girlfriend, and presto! the friend rings the doorbell, eager to join the party. “Yes, it’s that kind of house,” Greta Garbo moans again through the darkness, her film loop having run full circle. “I hate men!”

2:35 Off to the side, along the wall of smaller peep show booths, is one large booth fitted out with several benches. The graphic on the screen says “Volume I: Advanced Sexual Techniques and Positions,” produced by the Sinclair Intimacy Institute. “Play video” is invitingly lit on the menu, but no one does.

It’s incredibly explicit and mesmerizingly boring.

2:37 Only one screen attracts a big group. “Celebrity Sex,” where the loop includes the infamous Paris Hilton video. A crowd of people stands around watching the tape. It’s incredibly explicit and mesmerizingly boring. She seems as intent upon displaying her manicure as her prowess, and the only visible part of her boyfriend is a little short on personality. But the audience stays with them, gaping, through the whole dull marathon. Then the tape switches over to a re-enactment of the John Wayne Bobbitt incident — and the crowd instantly scatters and vanishes like a school of fish dispersing at the arrival of a Great White Shark.

2:42 An unusual occurrence in the museum: an animated conversation between a man and a woman. They are standing in one of the little peep show booths, watching films of the faces of people having orgasms. These visitors are speaking loudly and unselfconsciously! They’re not afraid of being overheard! And, when overheard at closer range, they turn out to be speaking in Swedish.

2:46 Suddenly an audio track comes piping through the gallery. Some intrepid couple has pressed the “play video” button to start the instructional technique film. A recorded man’s voice confesses, with the kind of earnest faux-candor common in infomercials: “It seems that every time we make love, I’m still fumbling around in the dark.” And, not to be outdone, a woman’s voice announces “I know I could enjoy sex more if I just felt better about my body.” Several booths away, Greta Garbo moans out her disillusionment yet again.

2:50 Walking down the hall to Gallery 3, the soundtrack from the instructional video is still, plaintively, audible: “We’re here to take away the mystery and expose the beauty and depth of our organs.”

2:51 Gallery 3 isn’t a lab or a peep show; it looks like a museum. Glass display cases, labeled exhibits, overhead track lighting. The exhibit is called “Spotlight on the Permanent Collection.” Essentially, it’s an attic — a jumble of racy odds and ends. Scary-looking old gynecological instruments. Quaint sex-education pamphlets, for both schoolchildren and adults. Erotic Japanese and Indian prints, old French postcards, nude male bodybuilding shots, cells from animé movies, Picasso lithographs, burlesque and pinup photos. A baldacchino-like structure in the middle of the room: a bondage frame. Most people give it a wide berth, but the Swedish couple walks right in, talking and gesturing, gazing curiously up at the various joints and pulleys.

2:53 As with the bonobo soundtrack in Gallery 1 and the music in Gallery 2, this gallery is also filled with sound to create an audio privacy zone so people can speak softly to each other without being overheard. Here it’s the soundtrack of a documentary film about an artist who makes pornographic dioramas and movies using robots made from Barbies and GI Joes. “Most Barbies are resculpted. You sand ’em down, add a cranium,” he explains. “This is Madam Robot’s artificial insemination machine.”

2:55 A display of life-size dolls, including one called “Virtual Girl: The Ultimate in Sexual Reality.” Displayed along with her are various interchangeable accommodating attachments. “Ewwww,” says a female viewer, one of the few really audible exclamations of the entire afternoon.

2:56 In a nearby case, a model of a female torso made out of foam, shielded by a sheet of Lucite with holes cut out over the figure’s breasts. “PLEASE TOUCH GENTLY,” the sign says; but the breasts are cracked, gouged, nearly ripped off.

3:00 Gallery 3 is not a room people linger in. Mixed in with the jauntily kinky and the quaintly coy is an undertone of misogyny. Or maybe there’s just so much of this stuff you can look at in an afternoon. Or maybe people are tired of being so unnaturally quiet and polite.

3:02 A man and a woman hurry down the stairs, back to the lobby. At the bottom of the staircase is a security guard. “Did you see everything?” he asks seriously, as if a negative answer would require that he send the couple back upstairs to inspect whatever they might have missed. “Yes,” the woman says firmly. “We saw it all.”

Arts & Minds (Part 2 of 4)

Profiles in the Creative Economy: An economy isn’t about policy; it’s about people.

I spoke to four people who solve old problems with new methods, who discover old solutions to new problems. They are combining interests and information in innovative ways. In doing so, they are building new communities. None of this work happens in solitude. It all requires a critical mass of resources: intellectual, technical, economic, and artistic. While the reach of these enterprises is international, they are rooted in local communities that encourage cross-fertilization between different kinds of expertise, that find new paths for knowledge and intuition. Art and commerce are once again becoming more comfortable with each other. In this new atmosphere we are seeing the results of a convergence of these two basic human impulses. It is a whole new world.

Photo by Alex Budnitz.

Jill Kneerim: director and co-founder of Kneerim & Williams at Fish & Richardson

Jill Kneerim is a founding partner, along with John Taylor “Ike” Williams, and a director of the literary agency Kneerim & Williams at Fish & Richardson. The agency is based in Boston and has offices in Washington and New York. One of the most prestigious in publishing, Kneerim & Williams’ authors include former poet laureate Robert Pinsky, best-selling novelists Brad Meltzer and Sue Miller, and scholars Stephen J. Greenblatt, Caroline Elkins, Joseph Ellis, Dr. Susan Love, and Ned Hallowell. This year, the agency celebrates its 20th anniversary.

Deborah Weisgall: When you began, New York was the center of the publishing industry. Though Boston had two illustrious publishers, Houghton Mifflin and Little, Brown, pretty much every literary agent was in New York.

Jill Kneerim: When we first began, a lot of the writers said to us, Isn’t it a disadvantage for you to be in Boston, since New York is the hub of the publishing industry? I answered that an agent is only as good as her clients, and, if you’re good, everybody will pay attention. Now that question never arises. And communication has become much easier as well.

Deborah Weisgall: How much is Kneerim & Williams an outgrowth of the Boston intellectual community?